The Blonder Tongue Case Collection

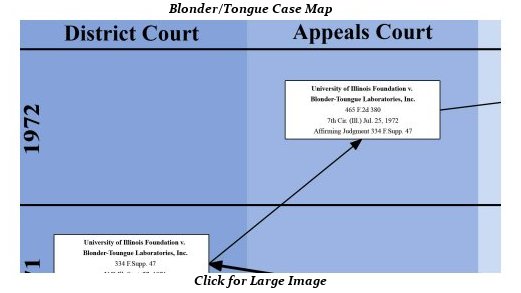

The CompanyBlonder Tongue Laboratories, Inc., located in Old Bridge, New Jersey, manufacturers a comprehensive line of electronic equipment intended primarily for the private cable television industry. The Historical Connection with Franklin Pierce Law CenterWhile in the service, Isaac "Ike" Blonder, one of the founders of Blonder Tongue became friends with another radar officer, Franklin Pierce Law Center founder Robert Rines, whose father was a patent attorney in the radio business. When the war was over, Blonder began to search for a job after he was decommissioned. It was Rines' father who suggested that Blonder visit Panoramic Radio Corporation, located in Manhattan. Still dressed in his army uniform, he observed a young man working on a band pass amplifier, and the two fell into conversation. The young man was Ben Tongue, and this chance meeting would lead to the eventual creation of Blonder Tongue Laboratories. Robert Rines also played an important role in the company's development. Rines, also given a stake, made a valuable contribution to the business as a patent attorney and adviser. Over the years, Tongue received 30 patents and Blonder 39. Robert Rines litigated the case that is the subject of this collection. The Background of the Case for This CollectionThis case is a landmark in patent law and in civil procedure in regard to collateral estoppel and modification of the mutuality of estoppel rule. The Court tried to strike a balance between the need to foster inventiveness by allowing patent holders to serially trying to enforce their patents and the need to eliminate bad patents by reducing the burden on alleged infringers. The Court reasoned that it is easier to determine whether a party had a full and fair opportunity to litigate an issue in a prior proceeding than to determine questions of patent validity. Therefore, that is where the initial focus is in patent cases in which the validity of the particular patent at issue has been the subject of previous litigation. This decision has been criticized for merely adding to the time and expense it takes to resolve patent validity issues, but several legislative attempts to revise the patent laws have failed to come up with a better alternative to this judge-made rule. In fact, the procedural rule of estoppel set forth in this case seems to be expanding to substantive areas of the law other than patents. The Procedural Posture Plaintiff University owned two patents by assignment for antennas designed for transmission and reception of electromagnetic radio frequency signals used in many types of communications, including the broadcasting of radio and television signals. It licensed the patents to a company that marketed the antennas. The University sued several companies that sold similar antennas for patent infringement. In one of those cases, the University lost because that court held one of the University's patents was invalid due to obviousness. Prevailing precedent at the time of trial in this case held that a ruling of invalidity in a collateral case did not estop the patent owner from enforcing the patent in a case involving a different alleged infringer due to the mutuality of estoppel principle. The University sued defendant in this case for infringement of both of its patents. Defendant asserted that both of the University's patents were invalid and counterclaimed against the University's licensee for infringement of its patented antenna. The district court held that both of the University's patents were valid and infringed. It also held that defendant's patent was invalid due to obviousness. Defendant appealed and the Seventh Circuit reversed on the issue of validity of the second of the University's patents, holding that it was invalid due to obviousness. However, the court affirmed the trial court's holding that the first of the University's two patents was valid. The Supreme Court granted certiorari to resolve the conflict between the courts that held the first patent invalid and the lower courts in this case, which held that patent to be valid. Explanation of Parties University of Illinois Foundation, Plaintiff-Respondent The University was the owner and licensor of two patents. The University was plaintiff in the district court, where it prevailed as to both of its patents. On appeal, the Circuit Court reversed as to the validity of one of the patents but affirmed as to the other. Defendant petitioned for certiorari and the University responded. Blonder-Tongue Laboratories, Inc., Defendant-Counterclaimant-Petitioner (B-T) was the owner and licensor of a patent for an antenna that competed with the University's antenna. It defended its customer, a licensee of its patent, against the University's patent infringement action. After the district court ruled for the niversity, it appealed. The Circuit Court ruled in its favor as to one of the University's patents but affirmed the validity of the other patent. B-T petitioned for certiorari. JFD Electronics Corp., Counterclaim Defendant-Respondent JFD was a licensee of the University and was a defendant in the counterclaim for patent infringement filed by B-T. The district court ruled in favor of JFD and it became an appellee in the Circuit Court. After the Circuit Court reversed as to one patent and affirmed as to the other, JFD joined the University in responding to the defendant-counterclaimant's petition for certiorari. Plaintiff claimed infringement of a patent previously adjudicated invalid. The trial court permitted relitigation of the validity issue because defendant had not been a party to the earlier invalidating judgment, and thus, under the doctrine of mutuality of collateral estoppel, could not claim its effect. The court of appeals affirmed, and defendant sought certiorari. The Supreme Court ruled that the trial court decision was vacated and remanded. The decision stands for the proposition that a Plaintiff whose patent was adjudicated invalid in a prior infringement suit may not relitigate the issue of validity against a different defendant, unless he can prove he lacked full and fair opportunity to pursue his claim in the original action. |

|