2010 Spring - Doctrine of Equivalents in Various Patent Regimes (Part 1) - Vinod Nama

I. Introduction

During patent infringement proceedings, the analysis performed by courts is usually divided into two steps: literal infringement and infringement under equivalents.

In the first step, the question is whether literal infringement is present or not, i.e. whether the challenger's product exactly falls within the boundaries of the patentee's claims or not. In the absence of literal infringement, a second step is that of interpreting the claims beyond their strict literal meaning, extending the scope of the claims to features or steps that are equivalent to those textually claimed. This second interpretation is usually referred to as the doctrine of equivalents (DOE). The DOE protects patent holders from copyists who seek to avoid infringement of patents by making minor, insubstantial changes to a patented invention. The DOE is controversial though. Some argue that patent protection is useless in the absence of such a doctrine since a claim would be limited to its literal language and easily avoided by a copyist[1]. Others argue that the doctrine subverts the statutory requirement that inventors particularly point out and distinctly claim the subject matter which is regarded as the invention[2].

When applied, the DOE includes consideration of the subject matter that was given up during prosecution of the patent. That subject matter may not be recaptured through the concept of equivalence. This limitation is called prosecution history estoppel. It prevents patentees from enforcing their claims against an otherwise equivalent feature in an accused device if that feature was excluded by way of amendments to the claims. Such amendment would have been effected during the prosecution of the application to distinguish the invention from the prior art. The scope, extent to which the prosecution history estoppel is applied varies in different countries.

The DOE is arguably one of the most important aspects of patent law. The protection a patent confers is meaningless if its scope is determined to be so narrow that trivial changes to a device bring it out of the bounds of the patent[3]. One of the greatest challenges courts and legislatures therefore face in patent law is to create rules for determining patent scope that maintain the protection a patent is meant to confer while still keeping the patent monopoly within reasonable bounds. Despite the general unity in patent laws among developed countries, the difficulty of this task has led to different results in different jurisdictions. Many jurisdictions have chosen to determine patent scope under DOE, while others have maintained the position that adequate scope can be found within the meaning of a patent's claim[4]. Even jurisdictions which agree that a DOE should apply differ significantly in its application. Because national law can differ between countries, the scope of patent protection provided by an international patent application may therefore vary widely from country to country. Although a traditional case of patent infringement under the DOE may find protection under various jurisdictions, the laws of these countries start to diverge on questions regarding the essential elements of a patent claim, and equivalents that clearly fall outside the language of a claim. Even the tests to determine non-literal infringement are not identical. There is significant convergence between the U.S., E.U., and Japan in claim interpretation and application of the DOE. Although Japan did not generally apply DOE a decade ago[5], now embraces the doctrine along lines similar to the U.S.[6] Similarly, the E.U. uses equivalents, which were written into the Revised European Patent Convention, to determine infringement[7]. This paper provides an observation of DOE laws of four patent jurisdictions—the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan while briefly highlighting laws of other countries as well.

II. What is the fight about?[8]

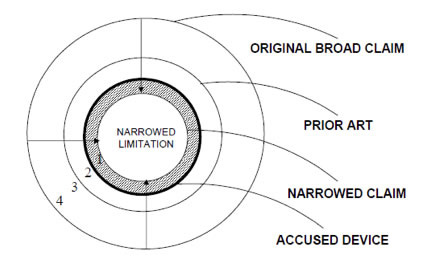

The above figure illustrates various aspects of patent prosecution process that may be relevant to the application of DOE. During the patent prosecution process, an original broad claim, which the examiner claims, reads on a prior art is narrowed down to exclude the subject matter of the prior art. In the process of narrowing the claim, the patentee relinquishes the subject matter of the prior art. The question is whether the accused device encompassing region 1, falls within this subject matter (region 4, 3, or 2) relinquished by the patentee or within the subject matter same or equivalent to the narrowed claim.

III. U.S. Position

A. Judicial Underpinnings for the Doctrine of Equivalents

The United States patent laws are found in Title 35 of the United States Code. § 271 deals with infringement. However, § 271 only codifies the statute on literal or textual infringement. The DOE is the result of case law, not statute. It evolved gradually as judge-made law.

The DOE has its roots in the United States Supreme Court decision in Winans v. Denmead.[9] The patent in Winans described a railcar with a conical cavity for carrying coal, resulting in an even weight distribution of coal in the car and a lower center of gravity. The accused railroad car had octagonal and pyramidal cavities instead, thus providing the same result as Winans's railcar without falling within the literal language of Winans's patent. The trial court found no infringement, but the Supreme Court found infringement, applying the following logic:

The exclusive right to the thing patented is not secured if the public are at liberty to make substantial copies of it, varying its form or proportions. And, therefore, the patentee, having described his invention, and shown its principles, and claimed it in that form which most perfectly embodies it, is, in contemplation of law, deemed to claim every form in which his invention may be copied, unless he manifests an intention to disclaim some of those forms. [10]

The DOE was firmly established in American law by the landmark decision of Graver Tank & Manufacturing Co. v. Linde Air Products Co.[11] (Graver Tank II). This case guided the United States DOE for almost the entire latter half of the twentieth century. The patent in Graver Tank II involved a welding process and claimed a welding flux containing a major proportion of alkaline earth metal silicate. The preferred embodiment disclosed in the patent was a flux that included a mixture of silicate of calcium and silicate of magnesium. The accused flux also used silicate of calcium, but substituted silicate of manganese (a non-alkaline earth metal), for silicate of magnesium. However, the patent specification taught that manganese, the metal used by the infringer, could be substituted for magnesium.

The Court found that, although the accused flux did not infringe the claimed invention literally, it did infringe under the DOE. The Court suggested that only insubstantial changes would be encompassed by the doctrine.[12] Accordingly, the Court affirmed the test for infringement under the DOE: a patentee may invoke this doctrine to proceed against the producer of a device ‘if it performs substantially the same function in substantially the same way to obtain the same result. This test is called as the function/way/result test.

In Warner-Jenkinson Co. v. Hilton Davis Chemical Co.[13], the Court indicated that every element of a claim is material and the function/way/result test for equivalents must be applied to each individual element and not to the claim as a whole. In addition, the Court indicated that each element must not be so construed as to effectively eliminate that element in its entirety. The Court then reaffirmed the doctrine of prosecution history estoppel as a limitation on the DOE, decided that equivalency should be decided at the time of infringement.

B. The Unforeseeable Equivalent Rule of Festo

Taking a cue from Judge Rader, the Court in Festo Corp. v. Shoketsu Kinzoku Kogyo Kabushiki Co.[14] (Festo) essentially adopted his foreseeability approach, but only when the inventor seeks to overcome what otherwise would be a prosecution history estoppel. The Court recognized that usually a patentee's decision to narrow his claims through amendment may be presumed to be a general disclaimer of the territory between the original claim and the amended claim. However, even if a patentee narrows a claim, he may rebut the presumption by showing that at the time of the amendment one skilled in the art could not reasonably be expected to have drafted a claim that would have literally encompassed the alleged equivalent. [15] Specifically, the Court stated that the patentee can rebut the presumption that prosecution history estoppel bars a finding of equivalence if:

The equivalent was unforeseeable at the time of the application; the rationale underlying the amendment may bear no more than a tangential relation to the equivalent in question; or there may be some other reason suggesting that the patentee could not reasonably be expected to have described the insubstantial substitute in question.[16]

On remand from the Supreme Court, the Federal Circuit, among others, made the following rulings regarding the issue of the applicability of prosecution history estoppel:[17]

First, it reiterated that: (1) a narrowing amendment made to comply with any provision of the Patent Act could invoke prosecution history estoppel; (2) a voluntary amendment could give rise to such an estoppel; and (3) a narrowing amendment was presumably made for patentability purposes, unless the record revealed a different reason for the amendment.

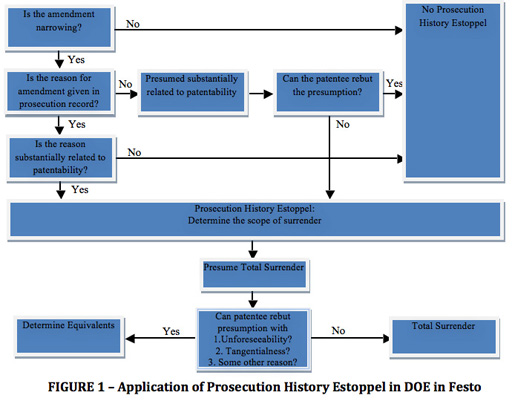

Second, it offered a framework for analyzing the applicability of prosecution history estoppel under the current law. The framework was posed as a series of questions, presumptions and conclusions that took the following form:

The court would examine an amendment and determine whether the amendment was a narrowing amendment. If the amendment was determined not to narrow the claim, then there could be no prosecution history estoppel. However, if the amendment was narrowing, then the court would have to ask whether the amendment was substantially related to patentability. In answering that question, the court would first have to look to the prosecution history record to determine if a reason for the amendment was given. If no reason was given, the court would have to presume that any narrowing amendment was substantially related to patentability, but a patentee would have the opportunity to rebut this presumption.[18]

If there was a reason given for the amendment in the record, then the court would determine if that reason was substantially related to the patentability of the claim. If the answer was yes, then prosecution history estoppel would apply and the court would have to determine the scope of the subject matter surrendered. If not, prosecution history estoppel would not apply. In determining the scope of surrender, the court would have to begin by presuming that surrender was total, and that none of the subject matter between the original claims and the amended claims could be used as an equivalent. This presumption, however, could be rebutted by the patentee. In order to rebut this presumption, the patentee would have to show that at the time of the amendment one skilled in the art could not be reasonably expected to have drafted a claim that would have literally encompassed the alleged equivalent. [19] According to the Supreme Court, a patentee could:

(1) show that the equivalent was unforeseeable at the time of the amendment

(2) show that the rationale underlying the amendment was only tangentially related to the equivalent in question or

(3) show that there was some other reason that the patentee could not have been reasonably expected to describe the substitute in the patent specification.[20] The following flowchart further illustrates the Federal Circuit's framework.

C. Conclusion

In any event, it is clear that in the United States an element subject to a prosecution history estoppel is subject to the reasonably foreseeable limitation whereas an element that is not may be expanded by any known or unknown equivalent. Whether the United States will adopt the reasonably foreseeable approach for all limitations is for the courts in the future to decide.

IV. Japanese Position

A. Background of Prosecution History Estoppel in Japan[21]

The Japanese patent system is originally derived from the German patent system and has been strongly affected by it. However, in terms of the DOE and prosecution history estoppel, the trends of the U.S. such as Warner-Jenkinson and Festo have strongly influenced those of Japan. Though the definition of prosecution history estoppel of Japan is similar to that of the U.S., there are some important differences between the U.S. and Japan. First, prosecution history estoppel has been used, not only in cases under the DOE, but also in the literal infringement cases. Second, prosecution history estoppel has been applied where an applicant had intentionally removed from the specification because the removed part was excluded from the technical scope of the patent. The intentional removal theory means that the intentionally removed part from the scope of the patent by applicant does not fall into the technical scope of the patent.

B. Ball Spline case

In 1998, Japanese Supreme Court affirmed the DOE first in Tsubakimoto Seiko v. THK K.K.[22] and it also mentioned prosecution history estoppel. The Supreme Court presented five requirements to apply the DOE:

(1) the differing elements are not the essential elements in the patented invention;

(2) even if the differing elements are interchanged by elements of the corresponding product and the like, the object of the patented invention can be achieved and the same effects can be obtained;

(3) by interchanging as above, a person of ordinary skill in the art to which the invention pertains could have easily achieved the corresponding product and the like at the time of manufacture etc. of the corresponding product;

(4) the corresponding product and the like are not the same as the known art at the time of application for patent or could not have been easily conceived by a person of ordinary skill in the art at the time of application for patent; and

(5) there is not any special circumstances such that the corresponding product and the like are intentionally excluded from the scope of the claim during patent prosecution.

In brief, the five requirements are:

- Essential Part[23]: An accused product or process deploys a variant that corresponds with a non essential element (the element of the claim that is not considered to be ‘essential' to the invention). In other words, if the variant used in the infringing device or process corresponds with an essential element of a claim, it does not infringe the claim in question, either literally or under the DOE.

- Interchangeability[24]: The object, the function and the effect of the invention can be achieved, even if there is a replacement of the claimed elements of the invention with elements of the allegedly infringing equivalent.

- Ease of Interchangeability[25]: The above interchange can be easily conceived of by a person of ordinary skill in the art at the time of manufacture of the allegedly infringing device or other exploitation by the accused infringer.

- Not Obvious from Prior Art[26]: The accused device is not part of prior art or ‘obvious' from such prior art to a person skilled in the art, on the filing date.

- No Special Circumstances[27]: There are no special circumstances, such as the fact that the accused device was intentionally excluded from the scope of the claim by the patentee during prosecution. Prosecution history estoppel is involved in this requirement.

The requirements (1) ~ (3) are positive ones and (4) and (5) are negative ones. There will be a finding of infringement only when all the five conditions are fulfilled.

C. Approach of Japanese judgments after Ball Spline case

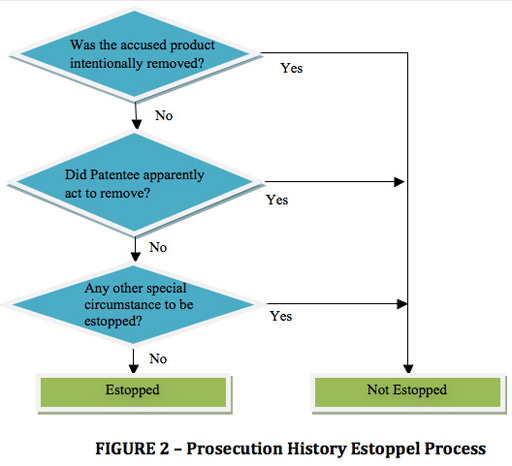

In Japan, courts initially determine whether or not there was an intentional removal from the scope of the claim during patent prosecution. Next, if it is not an intentional removal, courts determine whether the patentee apparently acted to remove from the scope of the claim during patent prosecution. Finally, if the patentee apparently did not act to do so, courts determine whether there is any other special circumstance to be estopped. To determine prosecution history estoppels, courts at least apparently have not scrutinized whether the amendment of the scope of the patent is related to patentability like the U.S. courts have done. Where an intentional removal exists, prosecution history estoppel is invoked. On the other hand, there is the opinion that even if an intentional removal existed, a patentee still may be able to insist on infringement under the DOE. The following flowchart summarizes the prosecution history estoppel process[28]:

D. Conclusion

The steps for applying prosecution history estoppel of the Japanese judgments are quite different and simpler from the approaches in the U.S. It does not matter (1) whether the amendment narrowed the literal scope of the claim; (2) whether the amendment was made for a purpose unrelated to patentability; and (3) whether the patentability involved §112 and not only §102 and §103 etc.[29] The Japanese courts tend to judge cases by the totality of circumstances. In most cases, where application of the DOE was estopped because of the intentional remove, the courts determine the conclusion directly from the actual facts such as prosecution history. Therefore, the Japanese judgments seem to be vaguer than those of the U.S.

* Vinod Nama (MIP '10) Vinod received a degree in Computer Science & Engineering in 2000 from the PES Institute of Technology in India, and worked for several years as a software engineer and intellectual property counselor for SAP, AG before attending UNH School of Law. He has most recently been working as a patent agent for Straub & Pokotylo, and previously worked and interned at Blakely, Sokoloff, Taylor & Zafman

[1] Graver Tank & Mfg. Co. v. Linde Air Products Co., 339 U.S. 605, 607 (1950).

[2] 35 U.S.C § 112 (2000).

[3] Nicholas Pumfrey, Martin J. Adelman, Shamnad Basheer, Raj S. Davé, Peter Meier-Beck, Yukio Nagasawa, Maximilian Rospatt and Martin Sulsky, The Doctrine of Equivalents in Various Patent Regimes - - Does Anybody Have it Right?, 11 YALE J.L. & TECH., 261 (2009).

[4] See id. at 261.

[5] William T. Ralston, Foreign equivalents of the U.S. doctrine of equivalents: We're playing in the same key but it's not quite harmony, 6 Chicago-Kent Journal of Intellectual Property 179 (2007).

[6] See id.

[7] See id.

[8] John M Benassi, Claim Construction and Proving Infringement, PLI Patent Litigation 2006, 7 (2006).

[9] Winans v. Denmead, 56 U.S. 330 (1853).

[10] See id. at 343.

[11] 339 U.S. 605; see also 11 YALE J.L. & TECH. 261.

[12] See id. at 610.

[13] Warner-Jenkinson Co. v. Hilton Davis Chemical Co., 520 U.S. 17 (1997).

[14] Festo Corp. v. Shoketsu Kinzoku Kogyo Kabushiki Co., 535 U.S. 722 (2002).

[15] See id. at 725.

[16] See id. at 740-41.

[17] Maria Luisa Palmese, Estelle J. Tsevdos, Kathlyn Card Beckles and Patrice P. Jean, Federal Circuit Decides Festo on Remand from the Supreme Court, http://www.kenyon.com/com/files/tbl_s47Details\File Upload265\56\Festo.pdf (25 March 2010).

[18] See id.

[19] 535 U.S. at 740.

[20] See id.

[21]Makoto Endo, Comparative Study on Prosecution History Estoppel in the U.S. and Japan, CASRIP Newsletter, Autumn 2002, Part 1 of 2.

[22] Tsubakimoto Seiko Co. Ltd. v. THK K.K., 52-1 MINSHU 113 (Sup. Ct. Feb. 24, 1998).

[23] See Raj S. Dave, The doctrine of equivalents in various patent regimes—does anybody have it right?" at 49.

[24] See id.

[25] See id. at 50.

[26] See id.

[27] See id.

[28] See Makoto Endo.

[29] See id.

The Kenneth J. Germeshausen Center, created in 1985 through the generosity of Kenneth J. and Pauline Germeshausen, is the umbrella organization for Pierce Law's intellectual property specializations. Today the Germeshausen Center is a driving force in the study of international and national intellectual property law and the transfer of technology. It acts as a resource to business as well as scientific, legal and governmental interests in patent, trademark, trade secret, licensing, copyright, computer law and related fields.

The Kenneth J. Germeshausen Center, created in 1985 through the generosity of Kenneth J. and Pauline Germeshausen, is the umbrella organization for Pierce Law's intellectual property specializations. Today the Germeshausen Center is a driving force in the study of international and national intellectual property law and the transfer of technology. It acts as a resource to business as well as scientific, legal and governmental interests in patent, trademark, trade secret, licensing, copyright, computer law and related fields.